The five teenagers stepped up to their bowling lanes and flung their balls in unison.

No one got a strike, but no one seemed to care.

The five were cancer survivors enjoying a recent outing hosted by the CHOC AYA (Adolescent and Young Adult) Oncology Child Life program.

The boy in the middle lane wore a pink T-shirt and white shorts. He also had a capped tracheostomy tube and AFO (ankle foot orthosis) braces.

As supporters cheered, 16-year-old Kenny Avendano smiled sheepishly after knocking down seven pins as he got ready to toss his second ball.

Kenny had never bowled before.

For members of his large care team at CHOC, that Kenny was even alive – let alone bowling – was a wonder to behold.

Fight of his life

Many of the teen’s doctors, nurses, and others thought Kenny wouldn’t survive a harrowing infection he contracted after a bone marrow transplant to treat his leukemia.

His risk of dying was greater than 90 percent after surgery to mend his infected spine, says Dr. Antonio Arrieta, medical director of pediatric infectious diseases at CHOC.

“We knew the odds he was facing,” Dr. Arrieta says. “At one point we asked ourselves, ‘How much are we going to throw at this kid?’”

But Kenny persevered.

“What he went through is difficult to imagine,” says Michelle Greene, a licensed clinical social worker in oncology who had many end-of-life discussions with Kenny’s mother, Shendi Hernandez. “Honestly, I think Kenny is the face of resilience.”

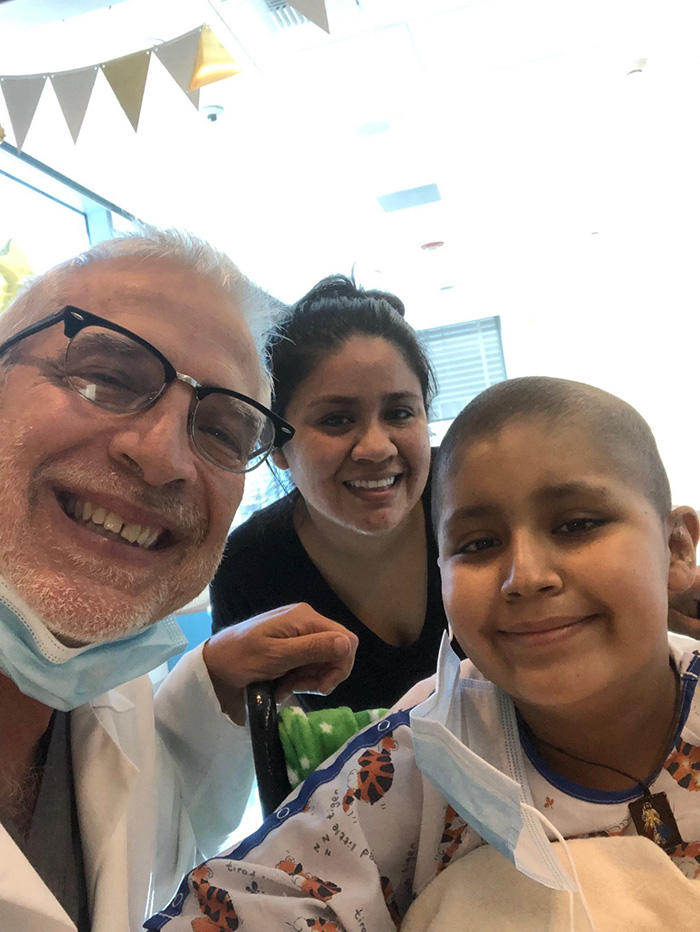

During a recent reunion with several members of the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) who treated Kenny during his darkest days two years ago, tears flowed and hugs were shared.

“Where’s your cape?” critical care Dr. Jason Cook asked Kenny. “You’re superman!”

True to form, Kenny cracked wise on his celebrity status at CHOC.

“This is my Lexus right here,” he said of his wheelchair. “I sign autographs every now and then. I need to start charging.”

Teamwork and coordination

From doctors to nurses to rehabilitation specialists to respiratory therapists to members of the palliative care and environmental services teams and beyond, Kenny’s health journey touched many areas of the CHOC enterprise.

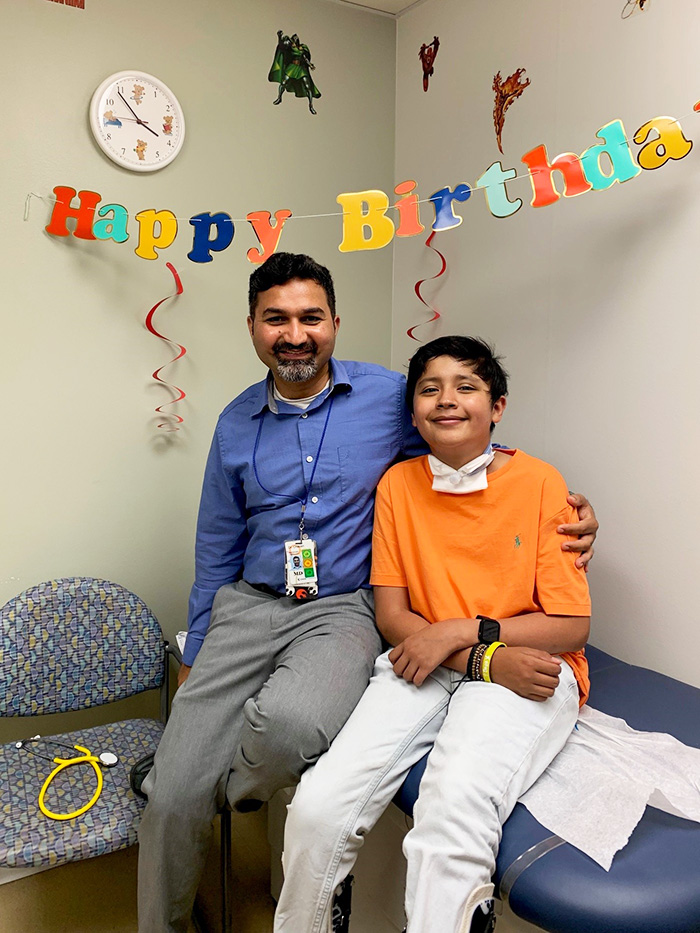

“His care truly portrays much-needed teamwork and coordination that we have at CHOC to take care of medically complex patients,” says Dr. Rishikesh Chavan, medical director of stem cell transplant and cellular therapy.

Kenny was diagnosed with leukemia by pediatric oncologist Dr. Van Huynh when he was 10, after he fell ill while attending science camp in the mountains.

An only child who loves math and volleyball and reading and all things concerning space travel, Kenny recalls asking him mom, “Am I going to die?”

“No,” Shendi told him. “They’re going to take care of you.”

A relapse

Kenny responded well to leukemia treatment and things were looking good as his 14th birthday approached.

But then, he relapsed.

“Everyone was heartbroken,” Michelle recalls.

Dr. Chavan performed a bone marrow transplant, with Kenny’s father, Daniel, serving as the donor.

But his post-transplant journey became very complicated.

‘You can’t get much sicker than that’

Chemotherapy wipes out the immune system, which can leave patients vulnerable to potentially deadly infections.

Unfortunately, 80 percent of children who don’t survive a cancer diagnosis die of an infection rather than the cancer itself.

This almost happened to Kenny.

A fungal infection that began in his lungs invaded his vertebrae. Another viral infection of the lungs made things worse.

Kenny spent eight months in the PICU after his transplant.

For a month, he was in a medically induced coma.

Dr. Jason Knight, medical director of the PICU, oversaw Kenny’s care there.

“He had a breathing tube and at one point, he was on the most ventilator support possible,” Dr. Knight says. “You can’t get much sicker than that.”

Keeping Kenny’s lungs alive was a treatment known as HFOV, for high-frequency oscillator ventilation. HFOV is used when conventional mechanical ventilation isn’t enough to do the job.

Surgeons removed a portion of Kenny’s right lung that the fungal infection had destroyed.

They inserted a titanium rod and 12 screws into his back to reconstruct three vertebrae where the fungal infection had come close to causing his spine to collapse.

A turning point

Dr. Arrieta says a key turning point in Kenny’s condition came when he put him on a high dose of a drug after identifying the secondary viral infection that attacked his once-strong body.

CHOC, Dr. Arrieta notes, is at the forefront of developing anti-fungal agents to combat infections like the one that gripped Kenny to improve the health of kids in Orange County, and around the world.

Still, for 48 hours, it appeared that Kenny wouldn’t make it.

Helping to care for him in the PICU was Dr. Sarah Keating, medical director of palliative care.

Dr. Keating started the palliative care program at CHOC for children experiencing medical care complexities like Kenny. Palliative care focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness.

“I look at the patient holistically, assess how they’re doing in the context of their medical condition, and then see what I can do to add support,” Dr. Keating explains. “I show up and ask, ‘How does that make your body feel?’ And I attend to the patient’s symptoms. My hope is to get things done so my colleagues can focus as much as possible on the disease process.”

Shendi says Dr. Knight was key to keeping her hopes alive as her son struggled to survive.

“I told her that every day that he’s still fighting and he’s not worse is a good day,” Dr. Knight recalls. “The next day she would ask me, ‘Is he better?’ I would tell her, ‘A little bit.’ We got to the point where, after two or three days, I thought he was actually going to survive.”

Says Dr. Keating: “It was quite an emotional experience because there wasn’t much of his body left. But his little lung cells just held on and kept breathing until, little by little, his body started to recover.

“The fact that he survived still blows my mind. No one can believe it.”

Grueling rehab

Because he was lying in a hospital bed for eight months and for one of those months was comatose, Kenny faced a grueling road to recovery after his condition became more stable.

Among his many ailments were serious cystitis (inflammation of the urinary system) and nerve damage in his legs and feet that made the seemingly simple act of having socks torturous.

“Most of his recovery was extremely painful for him,” Dr. Keating says. “He was profound in his ability to take it a day at a time and keep working toward getting better. It’s unbelievable how hard he had to work. No one could do it for him.”

Kenny was discharged from CHOC to HealthBridge Children’s Hospital, a sub-acute rehabilitation facility in Orange where many CHOC specialists serve on staff.

“I remember the first night Kenny was at HealthBridge and just trying to make him as comfortable as possible,” recalls Sandy Tuuao, a pediatric nurse.

When Kenny arrived at HealthBridge, he was on full support of the ventilator and also was on a lot of pain medications, including IV meds, says Dr. Patricia Liao, medical director at HealthBridge who cared for Kenny there as well as in the CHOC PICU.

Kenny was not able to stand – let alone walk.

“Initially, trying to get him off the ventilator for short periods of time was difficult given his understandable anxiety,” Dr. Liao says. “At the beginning, even a few minutes off the ventilator was a win.”

With his own perseverance, determination and joking personality, Kenny was able to get off the ventilator, wean off medications, and “walk out” of HealthBridge, Dr. Liao says.

“When we speak about teamwork in caring for a patient, his story exemplifies this,” she adds. “It was not one person but a whole healthcare team and family support that got Kenny to where he is today.”

Which is why, a year later, seeing him go bowling and walk around CHOC to visit members of his care team was so emotional for many.

“You’re walking!” exclaimed Dr. Liao, after Kenny got out of his wheelchair to strut around the lobby of the hospital.

Big plans

Kenny doesn’t linger on his most challenging times.

The 11th-grader at Tustin High School would rather focus on his next goal.

“I want to get my driver’s license,” he declares.

Kenny remains on nerve-pain medication for his legs. The braces are meant to shape his legs and feet into normal positions after months of atrophy.

Kenny now can walk short distances but gets winded easily, and balance is tricky. Pneumonia and infections have scarred portions of his lungs.

Soon, he will get his capped tracheostomy tube removed.

He has big plans.

“I want to be an aerospace engineer,” he says.

A huge mark

Kenny has left a huge mark on the doctors and

“It was a pleasure and a blessing to have cared for a great kid like Kenny,” Sandy says.

Says Dr. Chavan, who continues to see Kenny monthly: “Kenny has been and continues to be an inspiration for all of his caregivers at CHOC. He has a great attitude toward life and despite his highs and lows he’s experienced, he’s always smiling.”

Dr. Keating and others give a lot of credit to his mother for getting him through his health odyssey.

“The two of them are just extraordinarily close,” Dr. Keating says. “I think her love protected him. Medically, I can’t explain it at all.”

Dr. Arrieta notes there were many heroes involved in Kenny’s recovery at CHOC.

“I remember telling his mother at one point, ‘He’s going to walk out of this hospital,’” Dr. Arrieta recalls. “And he did.”

Get more expert health advice delivered to your inbox monthly by subscribing to the KidsHealth newsletter here.

Learn more the Hyundai Cancer Center at CHOC

CHOC Hospital was named one of the nation’s best children’s hospitals by U.S. News & World Report in its 2025-26 Best Children’s Hospitals rankings and ranked in the oncology specialty.