Life was proceeding right on schedule for self-described “drama kid” Genevieve Masson. The 16-year-old, who goes by “Geni,” went to class, hung out with friends and spent time rehearsing musical theater at her high school.

“It was really a normal, not-so-exciting life,” she says.

But two years ago, when Geni was 14, something changed. A small lesion that had been in her brain since birth began making itself known. One night, she woke up and couldn’t move. She figured she was caught in a moment of sleep paralysis and didn’t give it too much thought.

Things quickly turned far more serious. A few days later, Geni was feeling tired at school and decided to take a nap in her coach’s office. That’s when she had her first full-on seizure.

Geni has no memory of what happened next, but those around her became alarmed as her body shook uncontrollably. A teacher called 911 and the next thing Geni knew, she was in an emergency room.

An MRI revealed nothing, as did visits to pediatricians. But not only did the seizures continue, they were occurring more often. The more severe ones occurred at night, while less noticeable ones were happening many times a day. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with epilepsy, but she wasn’t receiving the expert care she needed at nearby hospitals.

“I remember the day she had her first seizure. It was December 18,” says Susan Masson, Geni’s mom. “By that January, there were a couple more. It got to be about 15 to 20 a day. We knew we needed to be at CHOC. We needed to be at a place where we could be with an epileptologist.”

The Massons felt lucky to live fairly close to CHOC, home to one of the nation’s premier epilepsy centers for young people. CHOC’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Program was the first in California to be named a Level 4 epilepsy center by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers, the highest level available. That distinction means that CHOC has the professional expertise and facilities to provide the highest level medical and surgical evaluation and treatment for patients with complex epilepsy.

It was at CHOC that the Massons met Dr. Maija-Riikka Steenari. A pediatric neurologist, Dr. Steenari is an epilepsy specialist, also known as an epileptologist.

“It’s a fascinating field,” Dr. Steenari says of pediatric neurology and epilepsy. “The combination of working with brains and kids together is the best fit for me.”

What exactly is epilepsy? Basically, parts of the brain go haywire and emit unwanted electrical signals that can cause convulsions and seizures of varying strength. As Dr. Steenari describes it, it’s “a clump of brain cells that don’t quite work the way they’re supposed to, or a cluster of cells in the wrong place. They’re really irritable. They’re known to cause trouble.”

Epilepsy can be the result of brain injury, stroke or, in Geni’s case, a slight anomaly that was present since birth.

November is National Epilepsy Awareness Month, a time to remind people that epilepsy is both fairly common — nearly 25% of the population will experience recurring seizures in their lifetime — and it’s often treatable.

Like others diagnosed with epilepsy, Geni’s first option was medication. She was prescribed anti-seizure medicines, but they didn’t work.

“Medication works about 60 to 70% of the time,” Dr. Steenari says. “But adding more medications doesn’t always work. A second medication only works about 10% of the time. So, can we do something else to help them with their seizures? That’s where surgery comes into play.”

Having seizures meant that Geni was missing a lot of school, would not be able to drive and couldn’t be left alone. But her family and friends rose to the occasion and helped when they could. And Geni did her best to be a regular teenager.

“I was trying to lead a normal life,” she says. “I would still go to rehearsals.”

Geni needed two surgeries, the first one to determine exactly where the problem was. Dr. Joffre Olaya was her pediatric neurosurgeon.

“We have these grids that we can put on the surface of the brain,” Dr. Steenari says. “We can map where the seizures are coming from within a few millimeters. We could make a very detailed map.”

The lesion was right next to the part of Geni’s brain that controls language. If her surgeon didn’t have an exact spot to operate, she could lose the ability to speak or write. But Geni was willing to take the risk. Each seizure could cause more damage to her brain and Geni wanted them to stop.

“The doctor said each seizure would do damage to my brain,” Geni said. “I don’t like having constant damage to my brain done. If surgery can take me back to where I can’t write or speak well, I was willing to take the chance.”

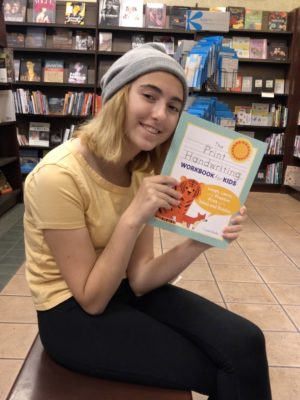

The second surgery came a few weeks later. Doctors successfully removed the lesion, but Geni faced a number of challenges after surgery that her family was told ahead of time were possibilities. Geni lost automatic movement of her right hand, so she couldn’t do with her right hand what other people do without thinking about it. She was 15 at the time, so before surgery, she had long ago mastered writing without thinking about how to shape each letter. After surgery, she knew how letters should look, but she couldn’t make them. She also couldn’t tie her shoes, brush her hair or teeth, button or zip her clothes, or feed herself. But Geni and her family treated these more like challenges than setbacks, and occupational therapy helped.

“A few weeks after surgery, we went to the library and we got some preschool books on how to write. It was quite frustrating, but luckily, my brain still knew how to do it. It just needed to create new pathways. As soon as I did it, it got easier,” Geni says.

Talking was hard after surgery, too. Geni would know what she wanted to say, but finding the right words took a little more time than it used to.

“Surgery had knocked over her file cabinet of words,” Susan explains of her daughter’s struggles post-surgery, which got better with speech therapy.

Geni’s family was with her every step of the way. It was heart-wrenching for her parents to see their daughter suffer, but they’re proud of how she handled her journey.

“I cry every time I remember how hard this was, and then I laugh at how much Geni thought it was simply annoying what she had to relearn. These kids are fearless little warriors,” Susan says of her daughter. “She’s a bubbly, vibrant, friendly girl. People love her. I don’t think it ever occurred to her that there was another way to manage through this. The limitations of life when you’re living with epilepsy can be staggering, but we didn’t have time to realize them. As soon as it came up, it ended. We got hit by a Mack truck and then it ended.”

Today, Geni has been seizure-free for 14 months. And while her right arm tires easily and she still sometimes has trouble finding the right words to say, someone meeting her for the first time wouldn’t notice.

“I have my driver’s permit and I’m learning how to drive,” Geni says. “That’s where I am right now. I’m working on a project for my film class and also an online play “Clue.”

Geni should continue to improve with time.

“She’s made remarkable recovery,” Dr. Steenari says. “She’ll continue to get better. If we had let those seizures continue, she would have ended up being much worse in the future.”

Get more expert health advice delivered to your inbox monthly by subscribing to the KidsHealth newsletter here.

Learn more about CHOC’s Neuroscience Institute

CHOC Hospital was named one of the nation’s best children’s hospitals by U.S. News & World Report in its 2025-26 Best Children’s Hospitals rankings and ranked in the neurology and neuroscience specialties.