How can parents support a child at home after they’ve attempted suicide?

By Megan White, Psy.D., CHOC post-doctoral fellow

While suicide awareness, prevention and support have increased across schools, workplaces, media and hospitals in recent years, suicide remains the second leading cause of death for children and young adults aged 10 to 24. Recent data from the Children’s Hospital Association’s Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) reports a 166% increase in emergency department visits for pediatric suicide attempts and self-injury between the years of 2016 and 2022, with almost 2 million adolescents attempting suicide each year.

When a caregiver becomes aware that their child has made a suicide attempt, is experiencing increased suicidal ideation (i.e., thinking about suicide and/or making a plan for suicide), and/or is showing signs that they are participating in life-threatening behaviors (e.g., self-harm, illegal substance abuse, risky sexual behavior, running away from home, etc.), it is recommended that they take their child to their nearest emergency room for a mental health evaluation.

After the evaluation, it may be determined that the child will need to be admitted for psychiatric hospitalization, in which the child will check in to a locked inpatient facility for immediate treatment. While admitting a child for intensive psychiatric care may not be something that families want to do, the 24/7 care that a child receives during a psychiatric hospitalization can give some caregivers a sense of relief. On the other hand, when a child is discharged from an inpatient hospital, families may experience feelings of anxiety, fear, anger and/or a sense of helplessness.

This article will focus on the main questions I hear most often from caregivers when their child is coming home from an inpatient program or other higher-level of care. It is my intention to (1) provide support to families during this stressful time, and to (2) reduce the odds of repeated suicide attempts and hospitalizations in the future.

Why is my child being released from the hospital if they still have suicidal thoughts?

- It is possible that a child will still have suicidal thoughts after being released from an inpatient hospital, since many times they are only there for a few days. So long as a child is no longer actively planning to hurt themselves and their family is in a place to provide supervision and keep the child safe, the child will most likely be discharged. This can be difficult for families (and patients!) to hear and accept. Unlike physical conditions or injuries that are often “fixed” in hospital settings, suicidal ideation may continue well after immediate hospitalization.

- As part of the discharge process, a child and their family will create a safety plan for the child’s return home. Safety plans will typically include a review of a child’s triggers, a list of signs and symptoms that a family should look out for, coping tools a child is willing to use to reduce intense urges to engage in life threatening behaviors, support systems for the child and family to reach out to, a review of how to physically safety proof the child’s home, and a confirmation from caregivers to provide 24/7 supervision for the child. If caregivers agree to what a safety plan requires and are able to confirm that they will follow hospital recommendation, then a child is “ready” for home.

- A child can have suicidal thoughts and keep themselves physically safe with the support of their families/loved ones.

How can I supervise a child with suicidal thoughts 24/7? I have a job and other kids, and also need to sleep and care for myself.

- The expectation to provide 24/7 supervision once a child returns home may feel overwhelming. However, supervision can be shared between caregivers and other trusted adults/guardians. Family members can take shifts being home with a child while caregivers go to work, run errands, and/or take care of their other children. Additionally, when a caregiver and child are home, a child can be in a room separate from a caregiver so long as there are regular check-ins (e.g., every 20 minutes lay eyes on child or get a verbal response from them if they are bathing/using the restroom). If the home is safety proofed (which families will be guided on prior to discharge), there is little need to worry about a child’s physical safety in any room of the family home.

- Sleeping arrangements can be determined by the family according to the child’s specific needs. Some arrangements that have allowed caregivers to maintain their child’s safety throughout the night are sleeping in the same bed and/or sleeping in the same room as their child. It is not recommended that a caregiver go without sleep to supervise their child throughout the night. Not only will this lead to burnout for caregivers, but also, increase discomfort and feelings of anxiety for the child.

- Note: Families are advised to talk to a child’s inpatient team about specifical barriers within their family home that may make supervision hard (e.g., other children, split households, work schedules, etc.) during the safety planning part of a child’s discharge. If caregivers/guardians do not feel like they can provide the level of supervision and safety that a hospital team recommends, more support may be needed before a child is discharged.

Does talking about suicide increase a child’s chances of attempting suicide? How can I assess their safety if I don’t want to talk to them about suicide?

- Talking to a child about suicide will not increase their suicidal ideation, nor will it create suicidal thoughts that were not already there. In fact, many of my patients have said that they wished their caregivers were morewilling to talk with them about their suicidal thoughts, as this would help them feel like suicide is a safe topic to speak about in their home.

- Avoid fragilization! Fragilization means to treat another person as if they are fragile or easily breakable, and therefore not able to handle hard topics, constructive feedback, or difficult conversations. Often, caregivers do not want to talk to their children about suicide or the emotions they have about their child’s mental health to not cause their child more stress and/or worsen their ideation. On the other hand, children do not want to tell their caregivers about their suicidal ideation to not worry or cause more stress for their caregivers or “burden them” in any way. By trying to not worry one another, family members accidentally make conversations around mental health taboo within their homes. Open communication between children and their caregivers allows for families to support one another rather than isolate. With open communication, children are more likely to feel like they can talk to their caregivers about their suicidal thoughts and to ask them for support without fear of causing a fight. This greatly increases a child’s ability to ask for help, and in turn, reduces the risk of another suicide attempt.

If my child tells me they have suicidal thoughts once we’re home, do I take them back to the emergency department?

- The short answer is: ALWAYS take your child to the emergency room if you have doubts about their safety and wellness. However, there may be steps that you can take before this to prevent another emergency room visit.

- If your child is telling you that they are having suicidal thoughts or thinking about suicide, it is more than OK to ask them what exactly they are thinking about. They have already told you it’s on their mind and bothering them, so they are likely open to talking with you about it. It’s also likely that they told you because they want to talk about it.

- If your child says that they are thinking about suicide, try to listen to the emotion and identify the emotion behind their statements. Are they angry? Are they sad? Are they worried or anxious? Are they feeling lonely or overwhelmed? Try to reflect what you’re hearing back to them in that moment. For example, “You’ve had such a hard week. You sound really overwhelmed and defeated right now.” Often, these are the big feelings behind suicidal thoughts and statements, and children may need support in expressing their emotions more than anything.

- Talking about what is causing suicidal thoughts may allow for a caregiver to support their child in processing and problem solving their emotions, and ultimately, coach their child through managing and regulating their emotional distress. Suicidal statements and thoughts are more likely to happen when a child is in “emotion mind” – or a mind state that is ruled by emotional thinking. So, helping your child regulate their feelings may decrease suicidal intensity in the moment.

- Taking your child back to the emergency department is the last step if you are feeling like you are unable to identify what your child is feeling, to gather information about whether they are thinking about a specific plan or not, and/or to rely on your safety plan to keep them safe. It is more helpful for a child to stay home and use their coping skills and support of family to get through a difficult moment and/or big emotions than to go to the hospital. Regulating themselves on their own will increase a child’s ability to independently manage big emotions, reducing risk in the long term.

How long should we follow our safety plan after a suicide attempt?

- There is no set amount of time that a safety plan must be followed. Again, this can be frustrating for caregivers and families to hear, as a safety plan often changes the way a family home is set up (e.g., making sure that sharp objects are put away and all medication is locked, sharing sleeping spaces) and how schedules are run (e.g., only one caregiver gone from the home at a time, changes in work schedules to allow for more time home, needing extra caretakers in the home). Caregivers and children may feel inconvenienced for a temporary period, and it’s worth it for the safety of your child.

- Typically, different parts of a safety plan may be eased depending on how a child is functioning at home. For example, if a child has gone 6 to 8 weeks without self-harming and/or reporting suicidal ideation, and caregivers feel that their child has shown an increased willingness to discuss their triggers and to ask for support when needed, perhaps some sharp objects may be introduced back into the home (e.g., kitchen knives for cooking, scissors for school or work, a razor in the shower so long as it is checked in and out with a caregiver). It is recommended that caregivers talk to their child about what sharps in the house are the most and least triggering for them, deciding as a team what a gradual reintroduction to “normalcy” may look like in the home.

- Children may “earn time alone” (e.g., sleeping alone, walking to school alone, having a sleepover at a friend’s house) depending on their progress in treatment, their willingness to ask for support, and their successful use of coping skills. Caregivers may also choose to share the child’s safety plan with trusted friends/relatives so that a child can leave their own home and still follow the safety plan wherever they are. If a caregiver is going to share a child’s safety plan with others, it should be discussed with the child beforehand. This is their treatment, and they may not want to share this information with others.

- It is recommended that families talk with their child’s mental health provider about safety plan modifications before changing plans. Ultimately, changes will happen when a family trusts that their child is ready to keep themselves safe. Trust is easily lost when a child makes a suicide attempt and/or lies to their caregiver about their level of risk or self-harming behaviors. It may take time to build back the trust that has been lost, and working with an outpatient mental health provider, like a therapist or psychologist, around how to rebuild this trust is often beneficial for families.

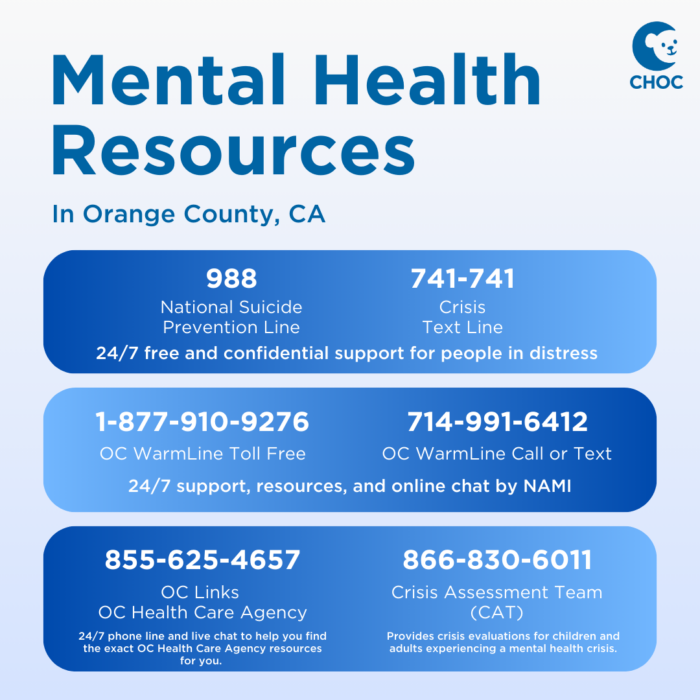

Mental Health Resources

for Orange County, CA

Download and print this card with a list of phone numbers to keep on hand in case of a mental health emergency.

Overall, when a child returns home after a suicide attempt, caregivers and children alike are likely to feel worried about what “normal life” will look like going forward. The questions discussed are by no means a complete list of what may come up for families during this period of time, and it is recommended that families talk with their child’s inpatient team before the child is discharged to problem-solve immediate questions and concerns.

It is important to remember that progress does not follow a straight path, and that talking about suicidal ideation and/or experiencing urges to self-harm does not mean that a child is moving away from progress or that treatment is not working. Remain consistent with your current treatment plan, take care of yourself, and consult with your child’s treatment team often.

Get more expert health advice delivered to your inbox monthly by subscribing to the KidsHealth newsletter here.

Get mental health resources from CHOC pediatric experts

The mental health team at CHOC curated the following resources on mental health topics common to kids and teens, such as depression, anxiety, suicide prevention and more.