When Noah was born last May, his parents Lauren and John were expecting a healthy baby boy. They were shocked to learn that prenatal ultrasounds had missed his pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA-IVS), a condition where the right side of the heart is underdeveloped, and there is no connection from the heart to the lung, compromising blood flow to the lungs and other parts of the body.

Noah’s pulmonary and tricuspid hypoplasia means that he was born with birth defects of the pulmonary and tricuspid valves, which control blood flow to the right side of the heart and eventually to the lungs. He was also diagnosed with a right coronary artery fistula, an abnormal connection between the coronary artery carrying oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

“When I was pregnant, I did everything I was supposed to do to grow a healthy baby. I gave up caffeine, ate well, and took the stairs every day to the ninth floor until I was 33 weeks pregnant,” says Noah’s mom Lauren, who is a pediatric occupational therapist at CHOC.

The evening Noah was born, he had low oxygen and platelet levels and was brought to the neonatal intensive care unit within the hospital where he was born. Dr. James Chu, a CHOC pediatric cardiologist who was making rounds that evening, suspected Noah had a pediatric heart defect and ordered a cardiac ultrasound, or echocardiogram, a non-invasive procedure used to assess the heart’s structure and function.

Dr. Chu returned to Lauren’s room as soon as he had a better idea of Noah’s diagnoses, even though it was 3:00 a.m. He knew Noah’s parents wanted to know what was wrong as soon as possible.

“He drew us diagrams and gently explained Noah’s exact heart defects, their severity, and detailed the surgeries he would have to endure,” Lauren recalls.

Dr. Chu told Lauren and John their son needed a higher level of care.

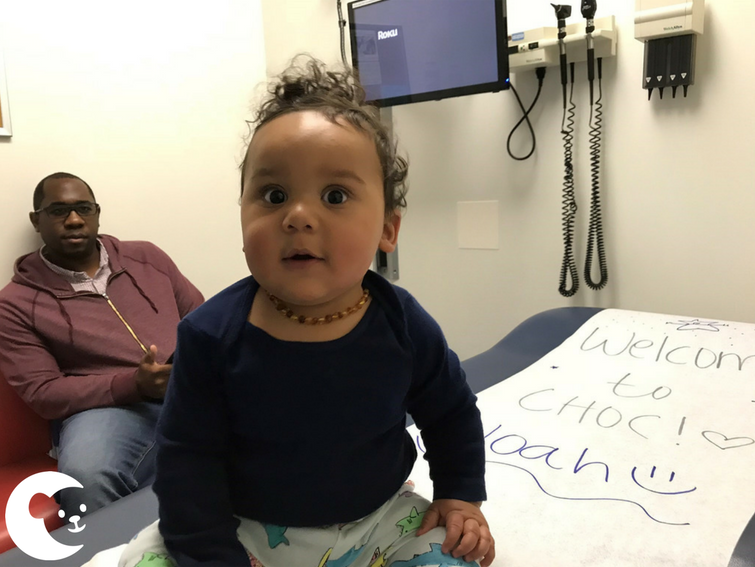

“He gave us a few options of where we could transfer Noah, and when I told him I really wanted to go to CHOC, he reaffirmed my choice,” Lauren recalls. “Once we arrived at CHOC, another cardiologist, Dr. Ahmad Ellini, confirmed the diagnoses, explained everything again, and answered all of our questions.

“We didn’t have a lot of time to think about a game plan immediately after he was born,” Lauren says of Noah’s surprise heart conditions. “But I knew that CHOC was the best place for him to be.”

Surgery for PA-IVS

Noah spent a week in CHOC’s NICU before undergoing his first in a series of three pediatric heart surgeries. That first week was an emotional rollercoaster, Lauren recalls. Noah’s team of neonatologists, Dr. Amir Ashrafi, Dr. John Cleary and Dr. John Tran, helped his parents remain calm.

“The team of neonatologists were great. They answered all my questions, spent lots of time with us, and were super available― even if I had a question at 2:00 a.m. Everyone on his care team was very collaborative,” Lauren recalls, adding that she found the attention to detail and calm nature of Dr. Richard Gates, director of cardiothoracic surgery and surgeon-in-chief at CHOC, very comforting. “Dr. Gates knows his patients through and through. Even though I have a medical background, I’m still a parent. He describes things in a way my husband and I understand, especially when we’re sleep deprived and scared.”

Babies with PA-IVS typically undergo three procedures:

- Blalock-Taussig (BT) shunt: a surgeon inserts an artificial tube to aid blood flow to the lungs. This procedure is usually done in the first week of life.

- Glenn procedure: Usually done between 4–6 months of age, this operation allows blood returning from the upper part of the body to flow directly to the lungs without passing through the heart. Now the left ventricle only has to do one job, pumping blood to the body.

- Fontan procedure: Typically occurring between 2 and 4 years of age, this surgery connects the pulmonary artery and the inferior vena cava (vessel returning oxygen-poor blood from the lower part of the body to the heart), allowing the blood coming back from the lower body to go to the lungs. Once this procedure is complete, oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood no longer mix in the heart. The surgeon may leave a small connection between the oxygen rich and oxygen poor chambers (a fenestration).

Lauren describes Noah’s surgeries to her family as a “miracle bandage” since they will not make PA-IVS go away. Noah may need a heart transplant someday.

“When Noah was born his heart was the size of a walnut. Each of these surgeries are temporary, and it’s Noah’s job to keep growing, and eventually, to outgrow each of these repairs and need the next one,” she explains. “Unfortunately, these surgeries cannot make his heart “normal” and he’ll always have serious heart disease, but we’re so grateful we have these operations to give him the best chance possible.”

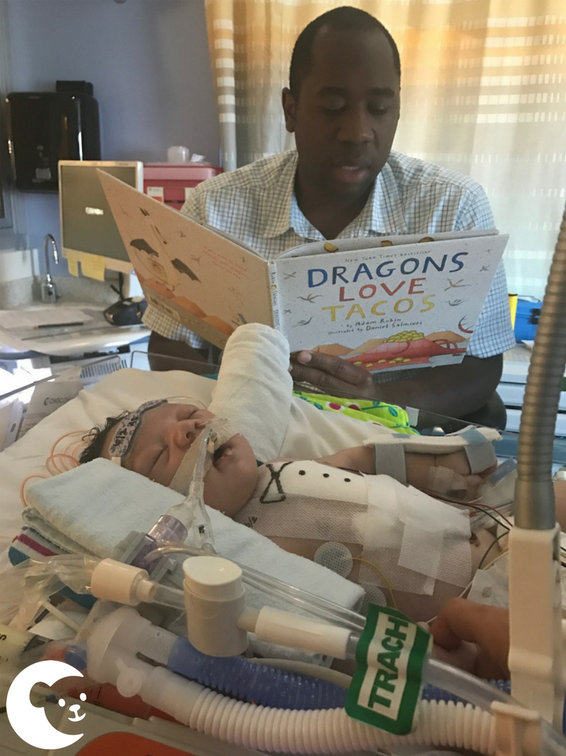

After his first surgery, Noah spent five weeks in the cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) at CHOC. For the first 48 hours of his recovery, he required extracorporeal life support (ECLS) (also known as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or ECMO), a special procedure that takes over the heart’s pumping function and the lungs’ oxygen exchange until a patient can recover from injury or illness.

“I knew there was a possibility he’d need to be on ECMO after surgery, but it wasn’t something I allowed myself to think about,” Lauren says. “It was hard to see him hooked up to so many machines and be so fragile. Dr. Joanne Starr did an extraordinary job managing Noah’s care while he was on ECMO and she also cared for us as his parents too. She checked on Noah at all times of the day and night, and even ordered me to go take a walk in the butterfly garden to get a break from being at his bedside 24/7.”

Dr. Starr, director of ECMO and medical director of cardiothoracic surgery at CHOC, has long been committed to caring for a patient’s entire family.

“In caring for children and teens, it’s vital that we as physicians remember we are not only taking care of the patient, but the parents as well. Parental stress and anxiety may have an effect on the patient and the healing process. If parents aren’t practicing self-care, they might not have a clear enough mind to be able to understand their child’s condition and make decisions on their behalf,” explains Dr. Starr. “Having a family’s full support is an important part of the healing process, and something that goes a long way in ensuring a positive long-term outcome for my patients.”

After five weeks in the CVICU, Noah’s parents were thrilled to be able to bring their baby home for the very first time. But a mere 30 hours later, they were readmitted to CHOC as Noah fought a central line infection.

Things calmed down a few weeks later. He went home, continued growing, and started hitting developmental milestones and developing a big personality. During the next few months, the family was still coming to CHOC as frequently as a few times per week for blood and platelet transfusions. Ever since Noah had a low platelet count at birth, his parents knew that he would need transfusions― they just didn’t know how many. That turned out to be as many as three transfusions per week.

Lauren and her dad had a history of donating blood. For instance, if they were at a hospital visiting a family member, they would always go find the blood donor center and give “because it was easy and it was just the right thing to do,” she says.

“I always knew that donating blood and platelets was important, but having a baby who needed blood and platelets changed my respect for what a gift it really is,” Lauren says. “When my baby needed to go on oxygen, and then they gave him a red blood cell transfusion and all of a sudden, he doesn’t need supplemental oxygen anymore, it’s a game changer. To literally watch a kid who couldn’t oxygenate well on his own, suddenly not need help breathing because of a blood transfusion, is amazing.”

Over the past several months, Noah has been able to meet several of the donors who have given him much-needed blood and platelets.

“It is so humbling to meet his donors. Whenever we come to the Orange campus for appointments, we visit the blood donor center and have gotten to meet and thank some of his donors,” Lauren says. “The people who give regularly are my heroes. Being helpless and not being able to cure your child is heartbreaking. We rely on these strangers and their generosity. They don’t know us, but they help us.”

The need for regular donors ―platelets especially― is so great because the shelf life on blood products is not long. Red blood cells have a shelf life of 42 days, but platelets only have a shelf life of five days, half of which is taken up by necessary safety testing before a patient can receive the donation. That means there is a window of about 48 hours where patients can receive donor platelets before they expire.

Direct donations, when blood and platelet donations are earmarked for specific patients, are an important way to safeguard patients who need ongoing transfusions, as they help minimize the number of different types of blood products they are exposed to during treatment. This will also help to improve Noah’s chances of being matched for a heart if he needs one in the future. Lauren outlined the ways donors helped her son in handwritten thank you notes she asked the Blood & Donor Services staff to distribute to his directed donors.

When Noah was about five months old, he underwent a cardiac catheterization procedure to determine if his heart was ready for the next surgery. This was standard protocol before part two in his series of surgeries, the Glenn procedure.

“It never crossed my mind that more bad news was coming because he looked ok. We thought he was doing fine,” Lauren says.

During Noah’s cardiac catheterization, his team noticed that the fistula in his heart had grown significantly in size. Noah’s “lucky fin” (as Lauren refers to his right ventricle) grew, which wasn’t good news for the left, healthy side of his heart. The weaker side of his heart was stealing space, blood and other resources from his stronger side. The discovery prompted the question, “Do we rush him into the Glenn procedure or go straight to a heart transplant?” ― a conversation his parents were not prepared for at the time.

“I didn’t even know what to hope for. Do we hope for the Glenn, or do we hope we find a new heart and a transplant goes well?” Lauren recalls. “His team told us to hope that his heart lasts as long as possible.”

His cardiology and hematology teams at CHOC rushed to help the family coordinate second opinions at other institutions within just a few days. They also helped the family coordinate a transplant evaluation, a three-part process to determine if the patient is medically qualified and the family emotionally prepared to care for a transplant patient.

“With invaluable input from a Southern California pediatric transplant team, and after multiple phone and in-person conferences amongst all his caregivers and his family, it was decided that Noah’s best chance at a positive outcome would be to have his Glenn procedure at CHOC,” recalls Dr. Ellini. “I have never worked at an institution that can so quickly mobilize to make sure that patients obtain the best care possible. It is even more amazing that our team at CHOC has the ability to use its regional resources to optimize the care of our complex patients like Noah.”

The consensus was clear―Noah needed a second surgery, and he needed it to go perfectly, or else he would need a heart transplant.

“That week rushing to get second opinions was a whirlwind,” Lauren recalls. “My husband and I were basically looking for any reason to stay at CHOC for surgery. Not only did we have complete confidence in Dr. Gates, but Noah’s entire care team has always treated him like he was their own child. There were so many people at CHOC totally invested in his care― everyone from cardiology, hematology, blood and donor services, the CVICU, everyone.”

After surgery, which went well, Noah stayed in the CVICU for 10 days before going home.

“I didn’t realize how hard he was working to just survive until after his second surgery,” Lauren says. “I couldn’t see how hard his heart was working to do anything because he was still happy, growing and meeting developmental milestones. But now I can just tell he feels so much better. He has more energy to play and skills are coming to him more easily now. It’s really amazing to see.”

The reason why Noah required platelet transfusions for the first few months of life remains a mystery. Thankfully, he hasn’t required platelets since his second surgery, when he was almost six months old, and his care team remains hopeful this is something he’ll grow out of.

Noah is slowly improving under the close watch of his hematology team, including Dr. Diane Nugent, Dr. David Buchbinder, Dr. Arash Mahajerin, Dr. Amit Soni, Dr. Victor Wang and Dr. Geetha Puthenveetil. Noah has an affinity towards Dr. Puthenveetil, whose last name means ‘Newhouse’ (Noah’s last name) in her home language. His family remains hopeful Noah won’t need any more transfusions, and his directed donors can now donate to help other CHOC patients in need.

Noah’s third open heart surgery, the Fontan procedure, will happen in a couple years.

Even though Lauren has been a valued CHOC employee for over four years, she knows the high level of care her son has received isn’t due to special treatment.

“We are treated like family here not because I work here, but because that is how CHOC treats all patients.”

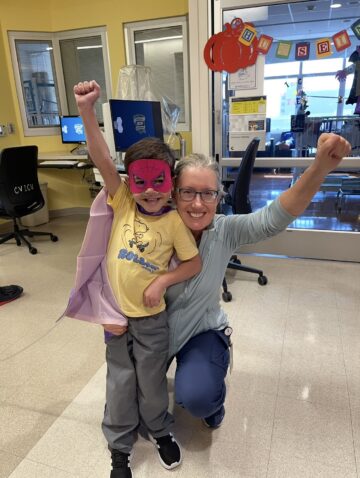

Today, one-year-old Noah is “defying all odds in terms of cardiac babies,” his mom says. He is very curious, always alert, and loves flirting with his favorite nurses.

Get more expert health advice delivered to your inbox monthly by subscribing to the KidsHealth newsletter here.

Learn more about CHOC’s Heart Institute

CHOC and UCLA Health together have been ranked among the top children’s hospitals in the nation for Cardiology & Heart Surgery by U.S. News & World Report.