Early signs and a diagnosis

Axel’s early days came with a few signs that something about his heart needed closer monitoring — small changes in his breathing, his coloring and his energy. Further evaluation confirmed the reason: tetralogy of Fallot, or ToF, a congenital heart condition involving four structural differences that affect how the heart delivers oxygen throughout the body.

Low oxygen.

Blue skin episodes.

A heart working harder than it should.

Babies with ToF typically undergo surgery within their first year of life, depending on each child’s symptoms and needs. For Axel, that moment came when he was just 2 months old, an early but essential step to support his heart and lay the groundwork for the care he would need as he grew.

Learning they weren’t alone

After the procedure, he was moved to the cardiovascular intensive care unit (CVICU) at Rady Children’s Hospital Orange County (Rady Children’s). Axel mentioned that those first hours felt overwhelming for his family, who found themselves navigating a world of monitors, specialists and constant uncertainty. But they soon discovered they wouldn’t be facing it from the sidelines. Each day, the Heart Institute’s care team invited them into the multidisciplinary rounds at Axel’s bedside.

Hearing the updates firsthand, asking questions and sharing what they were noticing helped his parents feel like active partners in his recovery, something that made an uncertain time feel a little more manageable.

There were still challenges ahead, but Axel’s family approached each one with determination and hope, encouraged by the support around them.

Early on, Axel’s medical team prepared his family for a wide range of possible outcomes, including the possibility that he might face significant developmental challenges. But slowly, with steady guidance from his care team, Axel began to chart a different course—one small milestone at a time.

Growing up with ToF

Axel grew up without a pulmonary valve, something the heart typically needs to move blood efficiently to the lungs.

And still, he pushes forward.

“I’m missing the pulmonary valve,” he says, “and I’m doing what I’m doing now — playing sports, going to the gym — without that pulmonary valve.”

Life as “the odd one out”

Along with his heart condition, Axel lived with Bell’s palsy, which affected the appearance of his face and caused facial paralysis. School could be tough.

“People would always ask me why I was born this way or why I looked like this,” he recalls. “I remember going home crying.”

But over time, those moments shaped him.

“I developed into a stronger person,” he says. “Now, none of that hurts me anymore. I’m proud of who I am.”

Outgoing, brave and honest — that’s how he describes himself now.

A turning point on the field

One summer during football practice, Axel’s heart condition resurfaced in a serious way.

He was lifting weights.

Pushing through drills.

Trying to ignore a strange feeling in his chest.

Then his body gave out.

“I thought my life was going to be over,” he says. “My mom told me my fingers were blue and I wasn’t responding.”

Doctors discovered he was having dangerous arrhythmias. Once again, his medical team acted quickly. And once again, he pulled through.

The moment changed him.

“I started taking life more seriously,” Axel says. “I became more grateful for everything I have.”

A doctor who walked the journey with him

Axel has been under the care of Rady Children’s pediatric cardiologist Dr. Nafiz Kiciman for nearly his entire life, a relationship that means a great deal to him.

“Dr. Kiciman was a big part of my whole journey and the reason why I’m still here. He saw me since I was a baby,” Axel says. “He saved my life. And everyone at Rady Children’s. They’re all heroes.”

His chest scar remains a reminder of what he’s overcome, and of the people who stood beside him.

Becoming a leader on and off the field

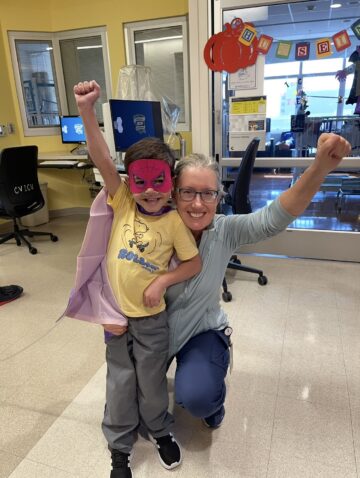

After recovery, Axel returned to football with a renewed sense of purpose. He wanted to lead in a way that mattered, especially for younger patients facing their own challenges.

“I know there are a lot of kids who think nobody understands them,” he says. “Sometimes they just need to hear from someone who actually went through what they’re going through.”

Even in the gym, he thinks of them.

“There are kids with heart conditions who can’t hit the gym,” he says. “So every rep I do is for them. If I fail, I remind myself … I can’t let one kid down.”

A heart built for leadership

Axel takes life as it comes, grounded in a perspective shaped by years of resilience.

“Challenges give us a reason to overcome them and become a stronger version of ourselves,” he says.

From a baby navigating a complex heart condition to a young man inspiring others, Axel has grown into someone his teammates and other heart patients can look up to.

“I know it hurts sometimes,” he says. “But if I was able to do it, I know other kids could do it too.”

More Heart Month stories

A heartbeat of hope: Meyer’s miracle year – CHOC – Children’s Health Hub

A heart of resilience: Three open-heart surgeries later – CHOC – Children’s Health Hub

Resilience and wonder mark heart-transplant patient Olivia’s journey – CHOC – Children’s Health Hub

Get more expert health advice delivered to your inbox monthly by subscribing to the KidsHealth newsletter here.

Learn more about CHOC’s Heart Institute

CHOC and UCLA Health together have been ranked among the top children’s hospitals in the nation for Cardiology & Heart Surgery by U.S. News & World Report.